Shareholder Activism in Canada is on the Rise

Activism in Canada on the Rise

Shareholder activism is on the rise again in Canada, and corporate boards and senior management are concerned. Activist defense is disruptive and requires significant time and resources. In addition, fending off an activist in the past does not make a company permanently immune.

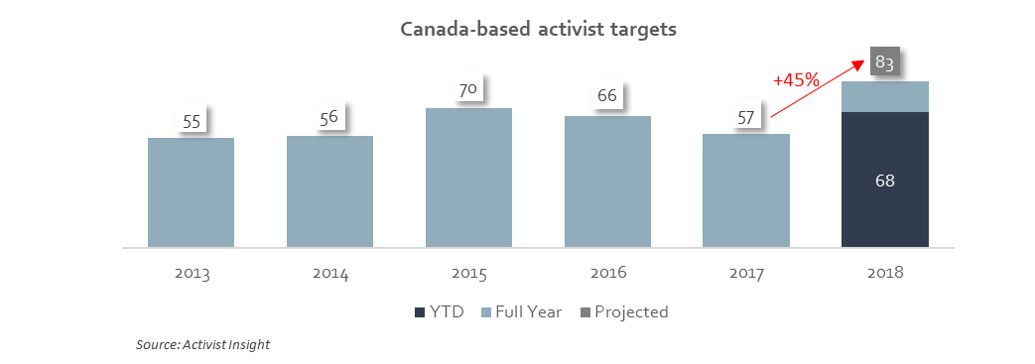

Shareholder activism started off as a U.S. phenomenon and has spread globally. In Canada, 57 public activist campaigns were waged in 2017; the second highest number outside of the U.S. The trend is expected to accelerate, with Canada-based companies publicly targeted by activists projected to jump by 45% for the full year. As of September 2018, those campaigns have already outpaced the number of campaigns for all of 2017.

The Canadian Activist Landscape

As activist campaigns began to emerge in Canada, they revealed some features of the Canadian regulatory landscape that differ from the U.S. Canadian corporate law has fewer barriers to activism than U.S. law. For example, shareholder access to the proxy process is more open in Canada. Shareholders with only 5% of the vote can force management to call a special shareholders meeting, whereas the percentages in the U.S. are generally much higher, ranging from 10% to as high as 51% depending on each company’s by-laws and/or state of incorporation. In Canada, a company’s entire board of directors is up for election each year. This differs from practice in the U.S. where many companies have staggered boards, where only a portion of the board, generally one-third, is up for election in any given year. This acts as a brake on an activist shareholder’s ability to take control of a company’s board. Those advantages to the activist investor are offset to some degree by the style of engagement with companies in Canada and various other features of Canadian law and regulation.

When activists mount public challenges to companies, a good deal of press attention is generated. What is less obvious is shareholder activism in private talks between investors and companies. Indirectly, the results of privately negotiated solutions may often be observed in changes to management or the replacement of directors. That distinction also applies to the role of activist investors in M&A transactions. For example, a merger or exploration of strategic alternatives is often driven by private discussions between large shareholders and the company.

Activism tends to move in waves and to focus on particular companies for specific reasons. Some of the factors that typically influence where activism occurs are:

- Underperforming sectors

- Underperforming companies

- Commodity price uncertainty

For example, long-time gold investor Paulson & Co. launched the Shareholders Gold Council in September 2018 along with 16 other notable investors in gold companies. The group has stated that it intends to engage with management teams on matters of compensation, corporate governance and capital allocation. This mobilization of a broad-based group of activist investors is unusual and will put a tremendous amount of pressure on the precious metals sector.

Preparing for Activists

Shareholder engagement, via consistent dialogue with long-term shareholders, can be the best and most powerful weapon against shareholder activism. This entails crafting a compelling long-term equity story and actively delivering the messaging through an ongoing outreach to existing shareholders. In addition, targeting new potential “long-only” investors can serve as a valuable counterpoint to activist shareholders. Measures include, but are not limited to, non-deal roadshows, conference participation, transparent reporting, investor relations responsiveness, and social media outreach.

Preparation, attention and shareholder engagement are critical elements of a proactive plan to mitigate the risk of investor activism. Senior management and the board must:

- ensure that the company maintains a good sense of the issues activists might raise;

- actively monitor changes to the company’s shareholder base and understand the motivations of each notable investor, particularly when M&A transactions are pending; and

- regularly review the company’s strategic priorities and ensure they are communicated to shareholders as well as to proxy advisors and rating agencies frequently and consistently.